AP Syllabus focus:

‘Women’s labor-force participation often rises with development, but this does not automatically create full gender parity.’

Women’s participation in the workforce increases as countries develop, yet gender disparities in opportunities, wages, and leadership persist, shaping uneven economic outcomes and influencing broader development patterns worldwide.

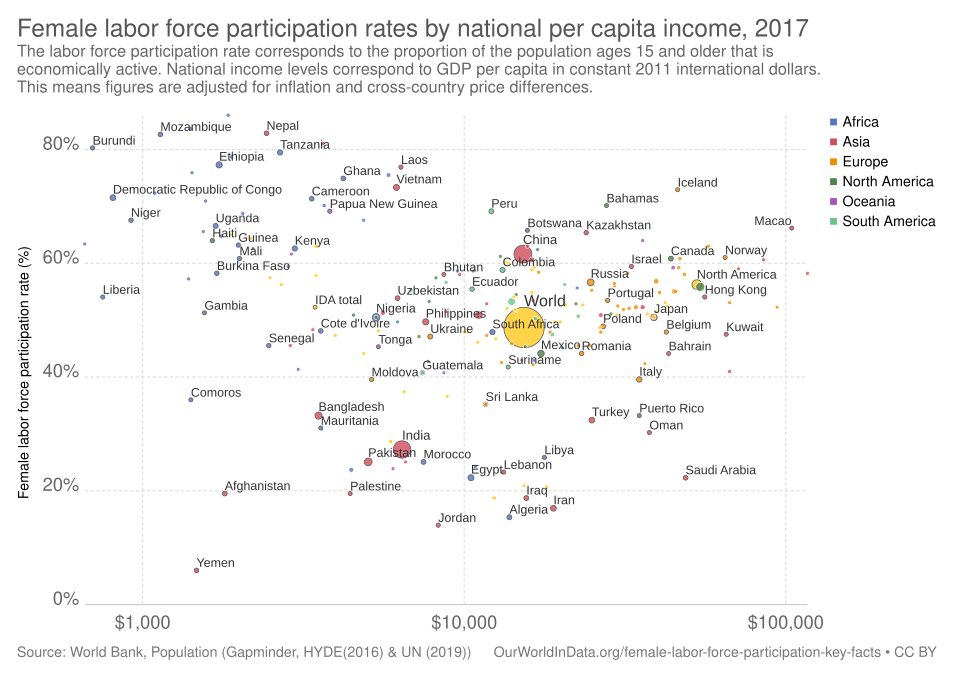

This scatter plot compares female labor-force participation rates to national per capita income for many countries. It illustrates that participation tends to increase as income rises, while still showing large variation between similarly developed states. The graphic includes more detail than required by the syllabus, such as specific income values, but directly supports the link between development and women’s participation. Source.

Women’s Workforce Participation in Developing and Developed Economies

Women’s labor-force participation refers to the share of women who are working or actively seeking work. As economies transition from primarily primary-sector (resource extraction) jobs to secondary and especially tertiary-sector employment, opportunities for women often expand due to shifts toward service-oriented and professionalized work environments.

However, higher participation does not guarantee equality. Gender norms, cultural expectations, and unequal access to education can restrict the kinds of work women enter, even when overall participation rises.

Key Drivers of Increasing Participation

Women’s growing participation is influenced by development-related changes such as:

Improved access to education, which increases qualifications for formal-sector work.

Urbanization, which creates new employment in retail, health care, and clerical services.

Declining fertility rates, providing more time and flexibility for paid work.

Legal reforms, including protections against discrimination and improved maternity policies.

As these conditions evolve, women shift into more diverse occupations, including professional and technical roles.

Understanding Gender Parity in Economic Contexts

Gender parity refers to the condition in which men and women have equal opportunities and outcomes in the workforce. Gender parity

Gender Parity: A state in which men and women have equal access to employment, wages, leadership positions, and career advancement opportunities.

While participation measures whether women are part of the labor force, gender parity measures the quality and equity of their participation.

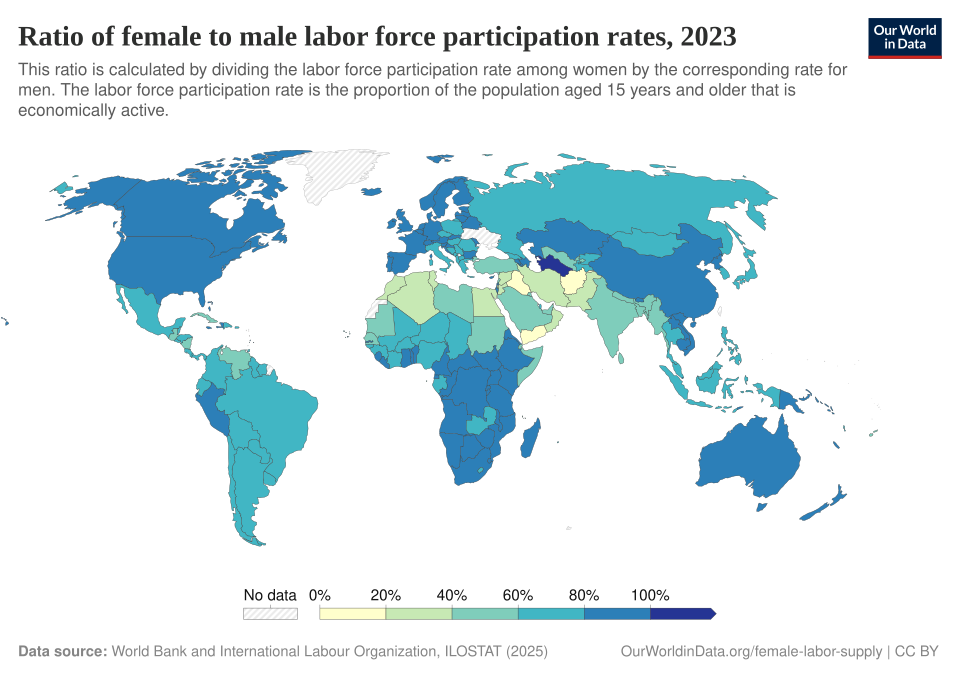

This map displays the ratio of female to male labor-force participation rates across countries. Darker shades indicate states closer to parity, while lighter tones show wider gender gaps. The map focuses specifically on participation ratios and excludes other gender-inequality dimensions not covered in this subsubtopic. Source.

Even in countries with high female participation—such as many high-income states—full parity remains uncommon.

Normal labor-force participation growth alone does not dismantle long-standing inequalities in job types, expectations, or mobility.

Persistent Employment Barriers

Even where economies grow and women enter work in larger numbers, structural and social barriers can limit advancement. These obstacles include:

Occupational segregation: Women are concentrated in traditionally “feminized” jobs (e.g., teaching, caregiving) that are frequently undervalued.

Gender-wage gaps: The average difference in earnings between men and women, often linked to discrimination and unequal career progression.

Informal employment: In many developing regions, women work in unregulated labor with low wages and no legal protections.

Unpaid domestic labor: Women typically spend more time on household and caregiving work, reducing time for paid employment.

Barriers to leadership: Fewer women hold managerial, executive, or political roles, limiting representation and decision-making power.

These structural inequalities reduce women’s economic security and slow progress toward equitable workforce participation.

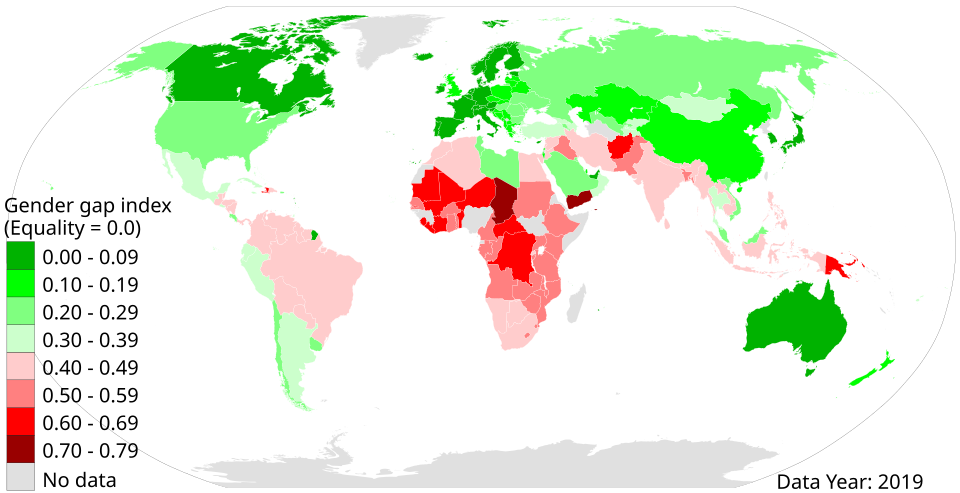

Measuring Gender Disparities in the Workforce

Understanding workforce inequality requires multiple economic and social indicators. The AP Human Geography course frequently uses measures that compare outcomes across gender groups. For example, the Gender Inequality Index (GII) captures reproductive health, empowerment, and labor participation, offering insight into national patterns of gendered opportunity.

This map shows Gender Inequality Index (GII) scores for countries worldwide. Darker red/orange shades represent higher inequality, while green tones indicate lower inequality. The map includes additional information—such as precise index values—not required by the syllabus but useful for visualizing global disparities that shape women’s workforce experiences. Source.

Because workforce disparities vary across space, geographers analyze how local norms, national policies, and global economic systems shape women’s work. This spatial approach helps explain why two countries with similar income levels can have very different gender outcomes.

Spatial Patterns of Women’s Participation

Geographers identify global patterns tied to cultural, political, and economic contexts:

High-Income Economies

Women often have high participation levels, but full parity is impeded by wage gaps, underrepresentation in executive positions, and glass-ceiling barriers.

Key characteristics include:

Widespread access to education

Dominance of tertiary and quaternary industries

Persistent leadership inequality

Middle-Income Economies

Participation is rapidly rising as industrialization and urbanization reshape job markets. However, women may still encounter:

Large informal sectors

Uneven legal protections

Societal expectations around family and gender roles

Low-Income Economies

Many women work, but often in subsistence agriculture or informal markets. Participation statistics may appear high, yet gender parity remains low due to:

Limited access to formal employment

Lower education levels

Cultural restrictions on mobility

These patterns illustrate that higher participation does not necessarily correspond to higher economic equality.

How Development Policies Influence Parity

Public policies play a central role in reducing gender inequalities. Policies that strengthen women’s economic security include:

Anti-discrimination laws

Paid parental leave and childcare services

Equal-pay legislation

Investment in girls’ education

Support for women-owned businesses

Such interventions can shift gender norms, expand economic opportunities, and improve the overall development trajectory of societies.

Globalization and Changing Opportunities

Economic globalization has created both opportunities and challenges. Manufacturing growth, service outsourcing, and expanding global value chains have increased demand for female labor in many regions. Yet these jobs may be low-paid or precarious, revealing a tension between increased participation and persistent inequality. Women’s integration into the global economy is therefore uneven, shaped by migration, industrial policy, and multinational corporate strategies.

Women’s labor-force participation often rises with development, but this does not automatically create full gender parity. Gendered barriers persist in wages, leadership access, and job quality, producing significant spatial variation in economic equity.

FAQ

Cultural norms influence expectations around childcare, domestic roles, and women’s mobility, which can limit their access to formal-sector jobs and career progression.

In some societies, social pressure discourages women from working outside the home, even when opportunities exist.

These norms may also restrict women’s movement, reducing their ability to commute or migrate for work.

Policies that support long-term career development tend to be most effective. These include:

Transparent promotion systems

Mentorship and leadership training

Targets or quotas in political or corporate leadership

Affordable childcare enabling continuous employment

These measures help women build the experience necessary for senior positions.

Flexible work can increase women’s participation by allowing them to balance paid labour with domestic responsibilities.

However, part-time roles are often lower paid, offer fewer benefits, and have limited paths to advancement, which can reinforce inequalities.

The overall impact depends on whether flexible work is well regulated and provides equal access to career progression.

Women in the informal sector often lack legal protections, job security, and access to benefits such as maternity leave.

Informal work also tends to involve low wages and limited opportunities for advancement, preventing women from gaining economic stability.

Because informal work is harder to regulate, governments struggle to implement gender-equality measures in these sectors.

Accessible and affordable childcare reduces the time constraints that push women out of the workforce.

Childcare availability allows women to take full-time or higher-skilled roles, improving long-term career prospects.

Public investment in childcare services is strongly linked to increased retention of women in the formal labour market.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which economic development can lead to increased female labour-force participation.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a basic link between economic development and increased female labour-force participation.

(e.g., development creates more service-sector jobs suitable for women)1 additional mark for explaining how a specific factor of development encourages women to join the workforce.

(e.g., improved access to education increases women’s qualifications)1 additional mark for providing a relevant, accurate detail or example.

(e.g., urbanisation expands retail and clerical employment opportunities)

Maximum: 3 marks

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how rising female labour-force participation does not necessarily result in full gender parity in the workplace. Use specific examples in your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks for identifying at least one clear reason why increased participation does not ensure gender parity.

(e.g., wage gaps, occupational segregation, or leadership barriers)1–2 marks for explaining how these inequalities persist even in countries with high female participation.

(e.g., women remain concentrated in lower-paid roles despite joining the labour force)1–2 marks for using accurate examples, patterns, or contrasts between countries or regions.

(e.g., Nordic countries have high participation and relatively high parity, while some middle-income countries show rising participation but large gender gaps)

Maximum: 6 marks